As I noted last week, the Affordable Care Act’s most prominent measure for the disabled was repealed in the fiscal cliff negotiation. The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act had many shortcomings. It was still a worthy and creative effort to help people live independently in the face of functional limitations. It’s not clear what (if anything) will replace it.

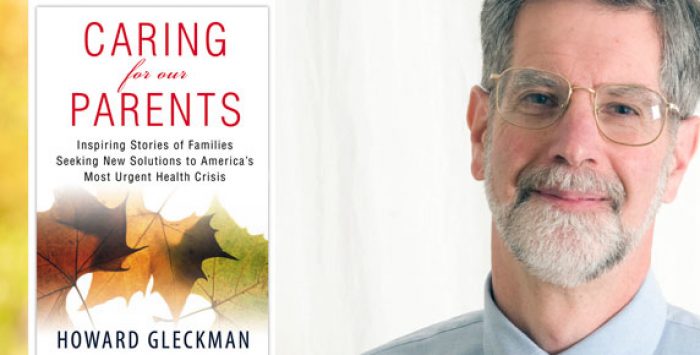

I spoke with the Urban Institute’s Howard Gleckman to explore what comes next in addressing our looming national disability challenge. Gleckman is one of the nation’s leading experts on family caregiving and long-term care. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

CLASS Act repeal was no surprise

Pollack: It was sad to see CLASS officially die yesterday. I take it you weren’t very surprised.

Gleckman: No I wasn’t. I did a blog post at the end of January of 2012 in which I predicted that CLASS would die sometime during 2012. I missed by a day. CLASS had very little political support. Republicans hated it, and there weren’t very many Democrats who liked it and were willing to go to bat for it.

The Obama administration never showed much enthusiasm at all – particularly after analysis showed that CLASS would require significant changes to be financially sound. Many of those changes would have required legislation, and there was no chance that Congress was going to fix it. So it was in limbo. When the Congressional Budget Office determined that CLASS could be repealed without costing any money, it was easy to repeal it, and that’s what they did.

Pollack: It’s discouraging. In the current environment, you just can’t go back and fix something when issues emerge.

Gleckman: There was a time when the common strategy was to pass a bill even if you knew it was flawed. You made compromises to get a bill passed. Then you fixed it. There’s no chance to do that anymore. That’s a problem with the broader health law, which contains other mechanically imperfect provisions. Things would work much better if they could be fixed. There’s just no possible way to do that. CLASS was a case study of that.

Time for a review of long-term care policies

Pollack: So what’s next? Now that CLASS has failed. Is there anything that’s going to come in its place?

Gleckman: The fiscal cliff law does create a new commission which is tasked to come up with a solution to the financing problem, and also to address delivery and workforce issues. This commission has a very broad mandate. It would have 15 members; three members would be appointed by the White House, three members would be appointed by the Democratic leader of the House, three by the Democratic leader of the Senate, three by the Republican leader of the House and three by the Republican leader of the Senate.

It’s a very important idea … We haven’t really done a good review of long-term care policies since the Pepper commission in 1990. It’s absolutely time that we do it again.

But this commission will be hamstrung by a very short time frame. Its members must be appointed within 30 days. The commission has to make its recommendations within six months after that. I honestly don’t think it’s possible to perform a serious review and deliver a set of serious proposals in six months.

It’s also concerning that this commission is not connected to any federal agency. Normally, you would think that something like this would have some connection with the Department of Health and Human Services, but it’s not. It’s floating around out there with no bureaucratic home.

There is also no requirement that Congress actually vote on any of these recommendations. The Commission is required to submit its recommendations in six months but Congress could ignore them. I don’t know where that leaves us.

Pollack: If anything, I think you’re wildly overoptimistic. It just seems like it’s going to head straight to the write‑only memory, as we used to say in engineering school.

Gleckman: I think that’s right. There are two reasons why Congress creates commissions. The first is that there is an intractable problem they want to get all the parties to sit down and work out. That was the case a few years ago, when there was a broad consensus that we needed to close military bases. The normal regular order of Congress wasn’t going to do it. So Congress turned it over to a commission. Everybody had agreed in advance what they wanted to do. Then there is the more common commission, which essentially is a way to make it look like you’re doing something when you’re really not. I fear that is what this one is.

Pollack: Although one bright spot would be if this commission could frame some important issues, That would have long‑term significance, even if the commission has very little operational influence in the short-run.

Gleckman: That’s the one benefit to this. If they can identify the nature of the problem and at least frame possible solutions, they’ll have accomplished something. What they won’t accomplish is coming up with a [specific plan] to actually fix the system.

Incentives for long-term care planning

Pollack: What would you like to see them recommend?

Gleckman: The first thing I’d like to see them do is actually acknowledge that there is a problem,… Then I think it’s a matter of framing the solution. In terms of delivery, I think it’s thinking about the relationship between long‑term services and supports and health care. Right now, we regard these as two entirely different things. Yet for recipients of care, people with chronic disease, these aren’t different. These are really one thing. We must recognize the need to better coordinate or integrate this kind of care. For the workforce, it’s obviously a matter of training and paying people a living wage and benefits. We just have to come up with the political will to do it.

I realize that the following is not shared universally. I would love to see us move from a “welfare‑based” system – which is Medicaid – to more of an insurance‑based system. What would that insurance‑based system look like? What is the role of the government? What is the role of private insurers?

I happen to think it would be much easier and probably much more efficient if we did it with an individual mandate. But I also recognize the political reality that we’re not going to get a mandated social insurance system any time soon. So the question becomes: Can you create enough incentives – both positive and negative – to convince enough people to buy insurance, to nudge enough people if you will, to buy government or private insurance so that they can begin to think about funding their long-term care, so they don’t find themselves in a situation where they have no insurance. Medicaid is not really capable of providing the kind of care that people want. So are there ways that we can anticipate this problem and use some sort of insurance system to begin to fund it?

Pollack: When you don’t have an individual mandate, this really undermines the policy. It also made it incredibly hard just to figure out what’s going to happen. There were really different analyses of CLASS out there. Who was actually going to sign up? What the premiums would have to be? And so on. Such uncertainties made CLASS a big risk from the point of view of policy makers …

Gleckman: That’s what happened with CLASS. Without a mandate, they took a shot in the dark, and they missed … You run into all the same problems that private insurance is running into. So you’re absolutely right. A mandate, for many reasons, would be a much simpler solution, but it just isn’t going to happen.

Are there better ways to use incentives? You’re not going to get the kind of risk pool you would get with a universal risk pool, obviously. You’re not going to get what you would get under a mandate. But can you get a risk pool that is diverse enough to make this work? Your question sort of suggests the answer, which is: We don’t know.

Convincing Americans to save for old age

Pollack: Now is there anything else we can do? Whatever CLASS’s shortcomings, it tried to address a real set of problems. If I need a ramp put into my house so I can live independently, that’s just not in the sweet spot of any of the public or private insurance products that are out there.

Are there any alternatives to ways that, right now, that people who want to live independently, who want to insure themselves against the possibility that they might need some intensive support services outside of an institutional environment, to make sure that they can get those?

Gleckman: The one obvious alternative would be if you could somehow convince Americans to save for their old age. If people do that, it’s their money. They would have ultimate flexibility to spend it on whatever they needed. But we, so far, have been unable to solve that mystery.

Pollack: There’s an “assume the can opener” aspect of that one, isn’t there?

Gleckman: The other possible solution would be to somehow link these services to health insurance? Right now, almost a third of Medicare beneficiaries are participating in managed care, Medicare Advantage plans. A significant fraction of the working population also participates in managed care of some kind. Now you have an insurance company that is fully at risk for the health care of its beneficiaries.

At least in theory there is an incentive for them to provide the kinds of supports and services that somebody with chronic disease could use to stay at home and to stay at home in as comfortable a way as possible. By doing that, the insurance company is potentially saving a substantial amount of money by keeping that person out of the hospital and keeping that person from having that chronic disease turning into acute episodes.

At least in theory, there is a possibility that you could take that managed care environment and do something very interesting with it. And provide some long‑term supports and services as part of a basic benefit. I don’t have a proposal, but I think there is an idea there. That’s something I’ve talked to some insurance companies about and people are chewing over, trying to figure out if there is a way to make it work.

Pollack: Thanks very much.

Tags: Affordable Care Act, Alzheimer’s disease, CLASS, disability, fiscal cliff, health reform, long-term care, Harold Pollack, Howard Gleckman