Pardon my ghoulishness with the following hypothetical.

Suppose that you were to slip and fall on your stairs, suffering a paralyzing injury. You want to stay in your home. But to do so, you might need your niece to spend 10 hours a week helping you out. She can’t really do that for free. You might need a modified van or a wheelchair ramp. How would you pay for these things?

If you needed more intensive services, how would you pay for that? Medicare covers some home care services. It doesn’t cover many critical items people will really need to stay independent. Medicare also doesn’t cover long-term nursing home care. Both public and private insurance leave huge coverage gaps. Home care and other services are financially draining. If you faced some disability, how would you cope without depleting your assets and relying on Medicaid?

About ten million Americans face some similar challenge. Maybe they’ve had a stroke or heart attack. Maybe they face early stages of Alzheimer’s. Almost 90 percent of people living with functional limitations live in the general community. It’s all scary stuff, for so many financial and human reasons.

These challenges were left largely unaddressed in health reform, with one little-known exception: the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act (CLASS). CLASS was precisely intended to help people live independently in the presence of disability. CLASS was complicated and shamefully under-covered. So you’re forgiven if you’ve never heard of it. (I covered this for the New Republic. It was a lonely beat.)

CLASS was designed as a national voluntary insurance program for working adults who might someday need help. It was not designed for the permanently nonworking disabled. People would basically sign up through their employers, paying monthly premiums based on age. No one would be turned away or charged higher premiums due to poor health status. After a five-year vesting period, people with specific functional limitations would receive cash benefits, on the order of $75/day. These benefits could be used to purchase specific services people require to live independently.

CLASS was designed to complement private long-term care insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and public disability programs. For Medicare recipients living in their own homes, CLASS would cover important services no one else would cover. CLASS benefits could also be used to help pay for a nursing home stay. Nursing home residents on Medicaid could keep some of CLASS’s daily benefits without compromising their eligibility.

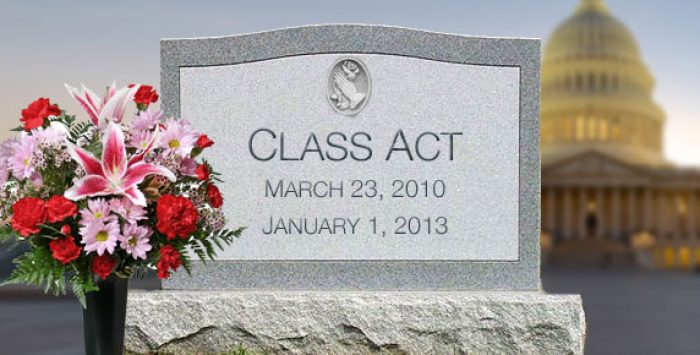

It was an appealing vision. I was planning to enroll myself. I guess I’ll need a backup plan. The fiscal cliff agreement, passed Tuesday night in the House, repealed CLASS.

Financial numbers didn’t work

Yesterday’s vote made official what many people already knew. CLASS died because the financial numbers didn’t fully work, because the White House didn’t want to expend scarce political capital to fix it, and because our current polarized political environment so often thwarts efforts to repair complicated programs whose imperfections become known.

This was a special problem for CLASS, because the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires CLASS to be self-financing. Premiums and benefits must be set to keep CLASS financially sound for 75 years. Republicans and many conservative Democrats hated CLASS from the start. Some of this debate reflected the usual health reform fight. Conservatives hated everything about the centerpiece initiative of the Obama presidency. Why should CLASS be any different? Well it was.

Health economists and actuaries draw upon decades of insurance market experience to understand how most parts of health reform will work and how much these provisions will actually cost. There’s never been anything close to CLASS on a national scale. Because CLASS lacked an individual mandate, it was hard to predict who would actually sign up, and how much things would cost.

Speculation about enrollment

The Congressional Budget Office was relatively optimistic. It estimated that about 5 percent of workers would enroll, and that the required average monthly premium would be about $123. Meanwhile, the federal government’s chief health actuary, a cantankerous nonpartisan official named Richard Foster, hated CLASS. He projected that only 2 percent of workers would sign up—a pretty unhealthy 2 percent, too. Foster’s office estimated that the program would require monthly premiums in the neighborhood of $180. Even now, it’s hard to say who was right on that.

Some powerful Democrats hated CLASS, too. Senator Conrad called CLASS “a Ponzi scheme of the first order, the kind of thing that Bernie Madoff would have been proud of. “Over Conrad’s objections, CLASS was included in the final health reform bill.

Conrad and others didn’t give up trying to kill it. And CLASS was dogged with other challenges. It needed strong buy-in from employers. It needed a serious worker marketing campaign. These pieces never really came together.

Administration’s heart not in it

In February 2011, two respected researchers, Alicia Munnell and Joshua Hurwitz, concluded that CLASS would require average monthly premium of $194. Various repairs were possible. The Obama administration’s heart wasn’t in it. That October, HHS Secretary Sebelius suspended CLASS.

CLASS remained on the books, but it was a dead man walking. Now it’s officially dead. Almost no one even noted its passing with everything else in the fiscal cliff mess.

That’s too bad. CLASS was a worthy, imperfect effort to address our looming disability problem. These problems aren’t going away. CLASS deserves at least a few mourners at its burial.

Tags: Affordable Care Act, Alzheimer’s disease, CLASS, disability, fiscal cliff, health reform, long-term care, Harold Pollack